The Sea and Its Strategy final two columns

Foreword

It is with great pleasure that the Royal Swedish Society of Naval Sciences publish this text by Captain (N) RSwN Lars Wedin (ret), also an honorary fellow of the academy. With his deep expertise, strategic perspective, and long experience on defence and security issues, he succeeds in clearly and concisely capturing the essence of the

challenges facing Sweden’s maritime interests and the challenges we face today.

At a time when the world around us is rapidly changing to the worse, with

demands for a quick and stable rearmament, we need reflection, orientation, and decisiveness. This text provides a sharp analysis and easily accessible guidance for the work ahead in connection with the decisions that must be taken at the NATO summit in The Hague. It is our hope that this text will contribute to continued insight and engagement in the debate on our maritime security and the defence of our nation and the alliance.

Royal Swedish Society of Naval Sciences Stockholm, June 15, 2025

Odd Werin

President

Introduction

This book consists of short summaries of each chapter in the book. The book will be published during the winter 2025–2026 by the Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences. So, there is still time to make necessary changes or additions. If you, dear reader, have anything you would like to change or add, please write to lars@wedinstrateg.fr

Why do I think it is necessary to write a book with the title The Sea and Its Strategy? One reason is that the Swedish public in general know too little about the navy, shipping, and our dependence of the sea. I devote quite a lot of time and space to the sea itself. Most books on naval strategy do not mention the sea at all, even though it is the object of naval strategy. Admittedly, Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s famous film is called “The Silent World,” but one should not take this film title too literally! Besides, the sea is definitely not silent!

The EU’s explanation why the sea is important is worth quoting, as it provides a kind of justification for the choice of title and subject. The sea is Europe’s lifeline. Europe’s seas and coasts are central to the continent’s well-being and prosperity – they are Europe’s trade routes, climate regulators, sources of food, energy and resources, and popular areas for settlement and recreation.

I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to my academic

fellows at the Royal Swedish Society of Naval Sciences and to Olle Neckman, who created the illustrations.

Combloux, May 31, 2025

Lars Wedin

Preface

Strategically, Sweden is an island. This does not mean that we are isolated – on the contrary, the sea does not divide, it unites as in the old latin words Mare conjugit, non separat. But the sea and its significance are relatively unknown, despite the fact that there are nearly 1 million pleasure boats in Sweden – almost one for every ten Swedes! This book is an attempt to remedy this lack of knowledge.

The book Havet och dess strategi (The Sea and Its Strategy) is intended to be scientific without being too technical. It aims to explain what maritime strategy and naval strategy are and why these concepts are important.

The book is intended for the interested public, but it is my wish that naval officers also will find it useful.

Let’s start by clarifying the difference between maritime and naval. The word maritime encompasses everything related to the sea: sailors, ports, ships, lighthouses…

as well as the sea and its inhabitants: such as fish, mammals and other animals. The word naval encompasses the security and defence-related aspects of the maritime domain, i.e., the Navy, which is part of a nations Armed Forces. From a strategic point of view, the activities of the Coast Guard are also included in the naval strategy.

The starting point is to first explain the connection between the sea and human beings and why this is important. We will then discuss the theory and practice of naval strategy.

In this book, strategy is defined as: Strategy is the science and art of manoeuvring the means of power to achieve political goals. But not just any goals – strategy is about manoeuvring in a situation characterized by (potential) conflict, where two or more states or other actors are manoeuvring to achieve their conflicting goals. Initially, the reader is presented with a reflection on the sea and human history – we will see how humans have learned to utilize the sea – not to master it, because the sea cannot be mastered.

We will then explore why the sea is important to us humans, to us Europeans, and to us Swedes. We will then narrow our perspective and consider the sea as a strategic arena.

Before we dive into the concepts of maritime and naval strategy, we need to familiarize ourselves with the concept of power and how it applies to the sea. From there, we will study these two types of strategy and try to understand how the three concepts of power, maritime strategy, and naval strategy are interrelated.

We then narrow the discussion further and tackle naval strategy, which brings us to peace, crisis, and war. First, we need to understand what characterizes war at sea. Next, we need some theoretical background, so we discuss the great naval thinkers: Mahan, Corbett, and their colleagues, both in the past and present. We will also look at how Swedish naval thinking has evolved over time.

We will then move on to the main section – maritime strategic tasks and the mostly used methods to solve them.

Maritime strategy does not, of course, exist in isolation from the state’s other interests. We therefore need to discuss how it relates to other strategies and policy areas.

We live in a time of rapid development, so what are the actual trends in naval warfare and how do they affect strategy? Hopefully, we now know quite a lot about naval strategy, its means and methods. We conclude this book with a reflection on Sweden as a maritime nation. Then there will be a few more chapters in the book!

Finally, why is all this important? Because the future of mankind, Europe and Sweden in particular lies in and on the sea.

Humans and the sea

Overview and main theme

This chapter deals with humans’ relationship to the sea throughout history, focusing on freedom, trade, conflicts, and culture. The sea is described both as a symbol of freedom and a source of danger, but also as a driving force for development, innovation, and contact through trade between people and cultures.

The freedom of the sea and threats to it

Historically, the sea has been regarded as the common property of mankind, where everyone has the right to travel and trade. This principle, formulated by the Dutch Hugo Grotius in the 15th century, is the basis for today’s United Nation’s law of the sea (UNCLOS). However, freedom at sea is currently threatened by several factors:

- Territorialisation, where states such as China and Russia are trying to expand their claims to international waters.

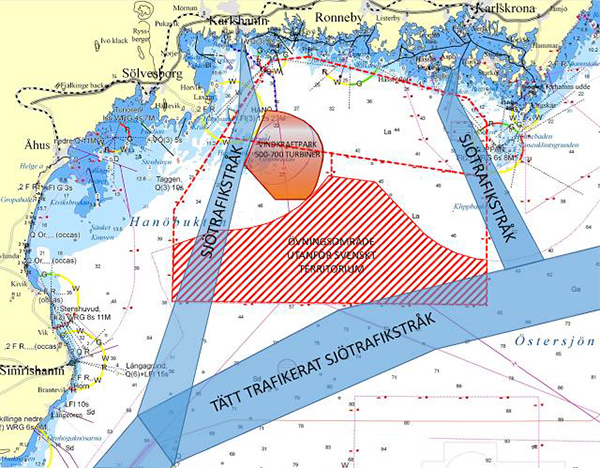

- Expansion of offshore infrastructure, such as wind farms and oil and gasplatforms, which r strict freedom of shipping.

- Security measures and environmental protection, which lead to new rules and geographical restrictions.

- Increased demands for protection of the marine environment, including establishment of marine protected areas.

Law of the sea and zoning

A nations internal waters are the area within the so-called baselines, that in principle follows the coastline. Here, the coastal state has full sovereignty.

- Beyond this lies the territorial sea, which is a maximum of 12 nautical miles (nm) wide. Here, the coastal state has sovereignty. Foreign vessels, including warships, may, however transit through the zone provided they comply with the rules on “innocent passage.” Submarines must transit on the surface.

- Beyond the territorial sea, the coastal state may establish an contiguous zone where it can practice certain rights regarding migration, historical artefacts etc.

- The coastal state may also establish an economic zone between the territorial sea and the high seas. This zone extends a maximum of 200 nm, and the coastal state has sovereign rights to explore and exploit the natural resources in the zone.In addition, the coastal state has jurisdiction over the construction and use of artificial islands and “installations and structures,” marine scientific research, and the protection of the marine environment. However, all states have the right to lay pipes and cables, etc. in this economic zone.

- The continental shelf gives the coastal state rights to the seabed, such as drilling for oil. The shelf normally stretches out to 200 nm from the coastline but can extend further out.

- The seabed outside the coastal state’s jurisdiction is called the Area and is the common heritage of mankind .

- 70% of the Earth’s surface is made up of international waters.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea states, among other things:

- The high seas are open to all states, whether they have a coastline or not. Freedom on the high seas is exercised under the conditions set out in the Convention and in other rules of international law.

- No state may validly subject any part of the high seas to its sovereignty.

- Every State, whether coastal state or not, has the right to freedom of navigation on the high seas.

The sea as a transport route and engine for development

For thousands of years, the sea has been the most important transport route for people and goods. Shipping has made voyages of discovery and the spread of ideas through trade possible. The importance of shipping for globalisation and economic development has been crucial, from the first voyages some 40,000 years ago to today’s container transport. At the same time, shipping has always been exposed to threats from pirates and conflicts between great powers.

Sweden’s maritime history

Sweden has a long tradition of seafaring and naval warfare. From the large boats of the Bronze Age, through the Vikings’ trading voyages to the east, to the navy and merchant fleet of the Great Power era. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Sweden was a significant maritime and trading power. After 1815, the role of the navy declined and the country adopted a more land-based defence strategy, which continues to have a negative impact on the Swedish strategic culture today.

The roles of the merchant navy and the navy

The merchant navy and the navy have historically been closely linked. A strong navy has protected trade, while shipping has been crucial to the country’s economy and the transport of needed livelihood of the population. During the world wars, the Swedish navy played an important role in protecting shipping and the country’s declared neutrality, but resources were often insufficient.

Culture and identity

The sea has been of great importance in literature, art and mythology. It has always inspired artists, singers and writers and has been a symbol of both hope and danger.

In Swedish culture, however, the sea has often been undervalued, both in historical research and in the strategic debate. The author argues for the need for a new strategic culture in Sweden, where the importance of the sea for the country’s security and prosperity is central.

Conclusion

The chapter concludes that the sea is both a goal and a means in a maritime strategy and that Sweden’s future security and development depends on that the country once again place the sea at the centre of its political and strategic culture. The sea unites rather than isolates, and its freedom must be protected against new and old threats.

Why is the sea important?

The seas are Europe’s lifeblood. Europe’s maritime spaces and its coasts are central to its wellbeing and prosperity – they are Europe’s trade routes, climate regulator, sources of food, energy and resources, and a favoured site for its citizen’s residence and recreation.

An integrated maritime policy for the European Union.

The central role of the sea for Europe and the world

The sea is the fundamental lifeline for Europe and the world. Europe’s seas and coasts are crucial for trade, climate regulation, food and energy supply, as well as recreation and settlement. International shipping drives the global economy, and globalization depends on the sea for the shipping of goods, people, information, and ideas. The sea is a global commons, together with the atmosphere, space, and cyberspace.

Economic and ecological facts about the sea

- 50% of the oxygen in the atmosphere is produced by the sea (phytoplankton).

- 60% of the world’s GDP is maritime related.

- 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered by the sea.

- 80% of the world’s population lives within 100 km of the sea.

- 90% of the world’s transport is by sea.

- 99% of all global information transfer takes place via submarine cables on the bottom of the oceans.

The total economic value of the ocean is enormous, and if the ocean were a country,

its GDP would be the seventh largest in the world.

Geography and dynamics of the ocean

The oceans have a complex and dynamic geography (bathymetry) with varying depths, currents, and ecosystems. Coastal areas are particularly important for human activity, trade, fishing, defence, and environmental protection. International maritime law regulates the nation’s rights to resources and exploitation of the continental shelf and economic zones.

The seabed and its resources

The seabed is rich in resources such as oil, gas, sand, minerals, and metals. However, extraction is costly and involves high environmental risks. Infrastructure such as pipelines, power cables, and fibre optic cables are strategically important and vulnerable to sabotage and accidents, as recently highlighted through several incidents in the Baltic Sea.

Environmental challenges and climate change

The oceans are threatened by pollution, overfishing, and climate change. Eutrophication, plastic waste, and emissions have a strong negative impact on ecosystems. The oceans absorb a large proportion of greenhouse gasses and heat, which leads to acidification, dying coral reefs and affects biodiversity and diminishing fish stocks.

Global warming is also causing sea levels to rise and extreme weather events to become more frequent.

Fishing and its challenges

Fish is an important source of protein globally, but overfishing and illegal fishing are major problems. Many fish stocks are overexploited and some have collapsed completely. Fishing is also a potential source of international conflict.

Maritime industries and the blue economy

The EU’s blue economy encompasses established sectors such as fishing, shipping, ports, shipbuilding, and coastal tourism, as well as emerging sectors such as blue biotechnology and marine energy.

Maritime industries are important for growth and employment and must be developed sustainably so as not to harm the environment.

The strategic importance of shipping

Shipping is crucial to the global economy and Sweden’s livelihood. Most Sweden’s import and export products are transported by sea. However, the Swedish merchant fleet has declined, which increases vulnerability in times of crisis or conflict. Shipping is also dependent on functioning ports and infrastructure.

Security and threats to the sea

The sea is an arena for conflict, hybrid warfare, piracy, and terrorism. Protecting critical infrastructure, such as cables and pipelines, is a growing challenge. Cooperation between civilian and military actors is needed to address these threats and to ensure freedom of movement and safety at sea.

Environmental protection and international goals

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 14 aims to conserve and sustainably use the oceans. This includes reducing pollution, protecting ecosystems, promoting sustainable fishing, and strengthening research and technology that contribute to healthier oceans. The EU and Sweden are working on strategies to protect marine environments and species, but the challenges are great and require international cooperation.

Conclusion

The ocean is crucial to mankind’s survival, economy, and environment. Its resources and ecosystems must be managed sustainably to ensure future prosperity and security. Sweden’s and Europe’s future is strongly linked to the health and safety of the ocean, which requires coordinated efforts at the national and international levels.

Power and Strategy

Sea power did not win the war itself, but it made it possible to win the war.

Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond.

When you master the sea, you master everything.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BC), Roman statesman.

Power and strategy

- Power is defined as the ability and willingness to change or exploit a situation to achieve a political goal. Power can be offensive (by influencing others) or defensive (protecting oneself from influence from other actors).

- Power is not only about resources but also about legitimacy, credibility and cultural influence.

- Effective power requires that resources can be mobilized and used strategically, and that the political project is supported by the population.

The nature of strategy

- Strategy is the science and art of using power to achieve political goals. It links action to effect and instruments to the desirable goals.

- Strategy is formed in a dialectical relationship between actors with conflicting wills, where each party adapts its strategy to the actions of its counterpart.

- Strategy is both a science (theories, historical lessons identified and learned) and an art (creativity, adaptation to uncertainty and friction).

Strategic levels

- Grand strategy (overall strategy) is broken down into military-strategic, operational, and tactical levels, each with its own goals and means to achieve the goals.

- There is no strict boundary between the levels; actions at the tactical level can have strategic and political consequences.

Manoeuvre and freedom of action

- Manoeuvre is the active part of strategy and aims to create advantageous situations through will, power and freedom of action.

- Freedom of action and economic utilization of resources are cetral concepts. Spreading resources too thinly leads to fragmentation of power and loss.

Offensive, defensive, direct and indirect

- Strategic manoeuvres can be offensive (changing to one’s own advantage) or defensive (maintaining an advantageous situation), as well as direct or indirect.

- At sea, the offensive is often stronger than the defensive, unlike on land

Means of power and goals

- Different means of power (military, economic, diplomatic) are combined to achieve political goals. It is the strategist’s task to choose the right combination and path.

- The political goal is paramount, and the strategy should lead to its achievement, but it is often difficult to translate military success into political success.

Seapower and maritime strategy

- Sea power is the ability to influence situations in the maritime domain to support political goals, and consists of the navy, merchant fleet, marine industries, etc.

- Maritime strategy is about using maritime means of power to contribute to the nation’s political and economic goals, including prosperity, resource utilization, and security.

- Naval strategy is a subset of maritime strategy and focuses on military aspects, such as maintaining a good order and security at sea.

Swedish and international context

- Sweden has historically had periods of strong naval power but has hardly been

a Thalassocracy (a maritime power in the cultural and political sense).

- An effective maritime strategy requires coordination between civil and military actors, as well as support from other policy areas (economy, education, diplomacy).

- International cooperation, particularly within the EU, is crucial for addressing common maritime challenges.

Conclusion

- Strategy is both a science and an art, and must always take into account changing circumstances, legitimacy and international norms.

- Sea power and maritime strategy are crucial to national security, prosperity, and the ability to influence international relations.

The Nature of Naval Warfare

It was an inhuman situation; [low ammunition, relatively slow speed due to damaged ships after four days of fighting enemy aircraft] but I have always believed that if the enemy is in sight at sea, air attacks or other considerations must be disregarded and the risks accepted.

Admiral AB Cunningham.

What could be more terrible than a battle at sea, where both fire and water unite to

destroy the combatants?

Vegetius (5th century AD).

Double challenge – the sea and the enemy

The naval sailor always faces two opponents: the sea, which is unpredictable and can never be tamed, and the human enemy. This duality characterizes all naval operations and justifies the need for a specific naval strategy, in addition to a common service strategy.

The Navy’s role in peace and war

The Navy and Coast Guard have important tasks even in peacetime, such as maintaining good order and security in Swedish waters and show presence. The transition time from peace to war is short – a few minutes. Each ship is an independent tactical unit, and the skill and initiative of the crew are crucial for survival and success.

Characteristics of naval forces

- Ships are expensive and take a long time to build, the same as it does to train the crews.

- They often operate far away from senior command, which requires initiative and independence.

- Orders are often sent from senior command by technical means such as satellite or radio communication.

- Cooperation with other domains (land, air, cyber, etc.) is required.

- Naval forces have great endurance and mobility, but distances at sea are even greater.

- They are dynamic and can quickly switch between combat, humanitarian

operations, and other roles.

Basic elements of combat

Naval warfare rests on three pillars: intelligence/surveillance/reconnaissance (ISR), firepower, and command and control. These interact to search for and defeat the enemy and protect friendly forces.The OODA loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) is used to describe the decision-making process in combat.

Weapon systems and forms of combat

- Air defence: Modern ships have advanced anti-air defence missiles and can act as floating command centres for air warfare (AW). New technologies such as micro-wave and laser systems are being tested to counter new threats such as drones.

- Naval targets: Anti-ship missiles are the dominant long range stand-off weapon system, but artillery and torpedoes are also used. Railguns and kamikaze drones are under development or in use.

- Submarine warfare: Submarines are characterized by their ability to remain hidden and surprisingly attack their enemies. They have advanced sensor systems and can carry both torpedoes

and anti ship and ballistic missiles.

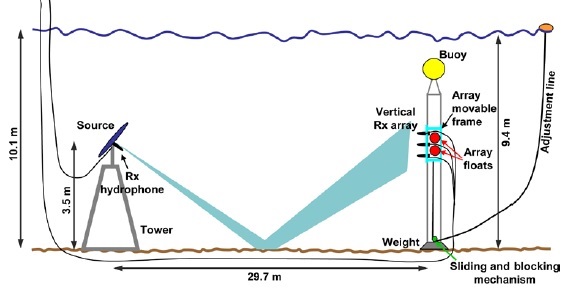

- Anti-Submarine warfare (actively search

for and destroy a submarine) is very

difficult and requires timely cooperation between ships, aircraft and helicopters, and sensors.

- Mine warfare: Mines are used both offensively and defensively and have become increasingly sophisticated.

- Mine clearance is nowdays often carried out by using a combination of manned and unmanned systems. Mine clearance takes long time, and full safety can never be achieved. Shipping in mine infested waters remains risky.

Combat against land targets and amphibious warfare

Ships can attack land targets with artillery and long-range missiles, and amphibious units can operate in the border zone between sea and land, especially important in archipelagos. These units must be able to utilize both the sea and land to their advantage in order to control important areas and routes of communications.

Command and coordination

Effective command and control of naval forces are crucial. Tactical commanders must be able to take correct and quick decisions under uncertain conditions and adapt to changing conditions. The balance between central control of naval forces and the freedom for the tactical commander is important to create and to encourage initiative and flexibility in combat.

Special features of naval warfare

- Naval warfare is characterized by:

- Speed and destruction in combat

- Short, intense combat phases within prolonged operations, sometimes over years

- Uncertain condition and the need to encourage initiative

- Differs greatly from land warfare, in special in mobility, intelligence collection, and vulnerability

Historical examples and lessons

Examples from the Falklands War, World War II, and the Cold War submarine intrusion and violations in Swedish waters illustrate how quickly war at sea can develop and how difficult it is to protect naval units against surprise attacks. Experience shows that the threat from the sea is constant and that technology, training, and tactics must constantly evolve and be developed as new technology is introduced.

Conclusion

Naval warfare requires special capabilities, technical systems, and understanding leadership. It is unpredictable, risky, and places high demands on both people and equipment. To understand and meet these challenges requires a deep understanding of the nature of naval warfare, technical expertise, and a constant adaptation to new threats and opportunities.

Naval strategic culture

The picture depicts Commander Daniel Landquist 1891 – 1972;

Sweden’s most prominent naval strategist.

La stratégie ne reste pas immobile… elle évolue légèrement. C’est, pour employer un terme désuet, une ‘variable amortie’. Mais elle se développe néanmoins. Il serait une erreur de s’en remettre à son immuabilité

Strategy does not remain motionless… it evolves slightly. It is, to use an old?fashioned term, a ‘dampened variable’. But it develops nonetheless. It would be a mistake to rely on its immutability. Amiral Raoul Castex, Théories Stratégiques, 1929–1935

Strategic culture and its significance

A strategic culture is about a country’s unique way of thinking about war and strategy, shaped by its historical experiences, technical resources, and geopolitical conditions. The Swedish naval strategic culture has been influenced by both national and international ideas and has often differed from other countries in its defensive orientation and emphasis on defending the country against an amphibious invasion from the sea rather than promoting own trade or offensive interests at sea.

International influences and theoretical schools

Swedish naval thinking has been inspired by foreign strategists such as Colomb, Mahan, Corbett, and Castex, as well as by French, British, and American doctrines. Various schools of thought are presented, such as the classical (focus on victory), neoclassical (broader sociological perspective), modern (social science view), and postmodern (criticism of linear relationships). The geopolitical, material, and scientific-rational methods are also discussed.

The development of Swedish naval strategy

- Since the end of the 19th century, Sweden’s naval strategy has been developed by several important thinkers and reformers:

- Anton Baeckström emphasized archipelago warfare and coastal defence, with

a focus on the utilization of equipment and tactical lessons learned from

contemporary wars.

- Carl-Gustaf Flach introduced the concept of “Fleet-in-being” in Sweden, which means that even inferior naval forces can pose a deterrent threat by avoiding combat and striking at the right moment.

- Daniel Landquist emphasized the importance of contesting the enemy’s naval supremacy and advocated a combination of defensive strategy and offensive tactics.

- Stig H:son-Ericson renewed the navy with Naval Plan 1960 (Marinplan 60), which focused on smaller, more manoeuvrable and agile naval ships and emphasized a deepened cooperation between the branches of the armed

- Claes Tornberg and Christer Hägg contributed to an intellectual revival of strategic thinking in the 1980s, with a focus on initiative, surprise, and operational mobility.

- Per Edling and Fredrik Hesselman have, in connection to Sweden’s NATO membership (2024), argued for a more offensive doctrine with a focus on maritime control and international cooperation.

Main lines of Swedish naval strategic development

- From the beginning of the 19th century, the main task of the navy was to defend the country from an amphibious invasion from the sea, control the archipelago and oddly support the army’s retreat along the large lakes towards Lake Vättern, where the final battle would take place in front of Karlsborg Fortress.

- During the 20th century, the strategy shifted between defensive and offensive approaches, depending on the geopolitical threat scenario and technological developments.

- During the world wars, protecting shipping became central, but after the wars, the focus returned to anti amphibious invasion from the sea. The experiences from the wars where quickly forgotten.

- The Cold War was characterized by a defensive strategy, supporting and cooperation with the army, while protection of shipping was deprioritised.

- In recent years, the need for maritime control and international cooperation has once again become central, especially after Sweden’s accession to NATO.

The role of education and debate

Education at both Swedish and foreign naval academies has been crucial to the development of Swedish naval strategic culture. A free and broad intellectual debate has been important in renewing and adapting the strategy to new geopolitical conditions.

Conclusion

Sweden’s naval strategic culture has been shaped by both domestic and international ideas and has been characterized by a shift between defensive and offensive strategies depending on the geopolitical situation. From being focused on protecting the coast and contesting enemy control, the strategy is now moving towards maintaining maritime control and participating in international operations together with allies and partners.

The Maritime Strategic Toolbox

Opportunity comes like a snail and disappears like lightning. Captain (N) RSwN Göran Frisk, commanding the anti-submarine warfare unit in the 1980s.

Hit first. Hit hard. Keep on hitting. Admiral of the Fleet, Sir John Arbuthnot “Jackie” Fisher, Royal Navy.

Angriff, angriff, angriff. Admiral Karl Dönitz

Strategic Theory and Doctrine

- Strategic theory is about understanding and formulating the basic principles for how naval power can be used to achieve political goals. Theory provides insights and guidance but gives no exact answers.

- Doctrine is the practical application of theory – official guidelines for how naval operations should be conducted. Good doctrine is based on theory, experience, and adaptation to one’s own capabilities and those of the adversary.

The objectives of naval strategy: Sea Control and Sea Denial

- The main objective of naval warfare is to use the sea for one’s own purposes

(Sea Control) and/or to deny the adversary this opportunity (Sea Denial).

- Sea Control means securing control over maritime communications to protect one’s own shipping and to enable offensive operations against the enemy posing

a threat to one’s own shipping.

- Sea Denial aims oneself to prevent the enemy from using the sea, without

necessarily having all the means to create full control. This can be achieved with fewer resources, e.g. through mines, drones or coastal missiles.

- Both Sea Control and Sea Denial are always local, temporary, and limited – total control is impossible.

Strategic methods

- Strategies can be sequential (step-by-step) or parallel (simultaneous), cumulative (many small efforts that together achieve the desired effect), or paralyzing (manoeuvre warfare to quickly knock out the enemy’s ability).

- Historical examples illustrate different strategic choices, such as decisive battles (which are rare), blockades, raids, and war of attrition.

Strategic tasks and naval functions

- Naval strategy means that a nation is being able to: gather intelligence, prevent threats, deter enemies, protect one’s own interests, intervene when necessary, and project power against land.

- Other important tasks include naval presence, blockade, defence/attack agai

nst sea communications, naval diplomacy, maritime security, and humanitarian operations..

- The protection of sea lines of communication and critical infrastructure, as well as intelligence gathering and surveillance capabilities, are also central in peacetime.

- Leadership and lessons from history

- Successful naval strategy requires strong leadership, an offensive spirit, flexibility, good intelligence and the ability to create surprise.

- Historical naval battles show the importance of decentralized command, coordination, endurance and the ability to adapt quickly to changing conditions.

Contemporary challenges and hybrid warfare

- Modern naval strategies must also address new threats such as hybrid warfare, where attacks on infrastructure, information warfare, and legal gray zone areas are central

- Maritime security today also includes protection against terrorism, piracy, environmental threats, and cyberattacks

Conclusion

Maritime strategy is an interdisciplinary discipline that combines theory, doctrine, historical experience, and practical application. It is crucial for protecting national interests at sea, contributing to international security, and dealing with both traditional and new maritime threats.

Dimensions, domains and interdependencies

More than other strategies, military or otherwise, naval strategy is rarely free. It may have freedom of action in the technical execution of certain operations, but very often it does not have it in the choice of these operations. Admiral Castex.

Dimensions

- Maritime strategy plays out in several physical dimensions: length, width, height (space above and below the surface) and time, which is crucial for movement and decision-making.

Naval forces operate on, above and below the sea surface and on the seabed,

where critical infrastructure such as cables and pipelines are also located.

- Deep sea operations are becoming increasingly important, particularly in terms

of protecting and monitoring infrastructure at great depths.

Domains

- Naval warfare is conducted in multiple domains: land, sea, air, space, cyber, electromagnetic, and cognitive.

- Each domain has unique characteristics and challenges, and an effective strategy requires coordination across multiple domains (Multi-Domain Operations, MDO).

- In addition to the traditional domains, the electromagnetic and cognitive domains are particularly important in modern naval warfare.

Special domains

- The space domain has gained increased military and civilian importance, including being used for communications, navigation, and surveillance. Commercial actors are playing an increasingly important role supporting these technical systems.

- Cyberspace is a virtual domain where information systems, networks, and digital operations take place. Cyber warfare is used for espionage, sabotage, and influence.

- The electromagnetic domain encompasses all use of radio signals, radar, and directed energy, and is central to both intelligence and combat.

- The cognitive domain involves influencing people’s thinking, decision-making, and moral, for example through propaganda, disinformation, and psychological operations.

Mutual dependencies (servitudes)

- Naval strategy is dependent on other strategies, such as industrial, economic, diplomatic, and legal strategy, and vice versa.

- Example: The navy needs an industrial capacity for its equipment, while the economy is dependent on open sea lines of communication for import and export of goods and commodities.

- Legal and political frameworks, such as international law, national regulations, and Rules of Engagement(ROE), regulate what military commanders can do.

- Multi-Domain Operations (MDO). Modern operations require coordination between the land, sea, air, space, cyber, electromagnetic, and cognitive domains.

- Prioritization problems and resource allocation between the different domains

are as always, a key challenge, but this is nothing new.

- Historical and contemporary examples show that successful leadership requires flexibility, an holistic view, and the ability to take initiative quickly.

- MDO makes for attractive PowerPoint presentation slides but is not new in itsel

- As early as 1900, the then Commander Herman Wrangel wrote that the branches of the armed forces are dependent on each other: It is precisely the constant flow of communication across the sea that can most easily be disrupted, even by a few warships. Herein lies the most important strategic link between a defending army and navy. The larger and more powerful the army are, the easier it is for the navy to fulfil its most important role, as long as it has freedom of action.

Conclusion

Maritime strategy must be seen as an integral part of a larger system in which several domains and dimensions interact and where mutual dependencies – between military, civil, technical, and legal factors – are crucial for success. An effective strategy requires both specialization within each domain and the ability to coordinate and see the big picture.

Humans and Technology in Naval Warfare

Ex Scientia Tridens – From Knowledge, Sea Power. Motto of the US Naval Academy.

The maintenance of ground combat units in Western Sahara during World War II took a continuous toll on the British small ships). “They were patched together time and again and needed extensive repairs, and could only be kept operational thanks to the enormous will and determination of the officers and crews in the engine rooms.

Admiral AB Cunningham.

Technology, Innovtion and Adaptation

Naval warfare is a human phenomenon in which the sea is the object, man is the subject, and technology is the means. For a navy to be successful, it requires both technical knowledge and the ability to innovate and adapt. Innovation is necessary in both peace and war but must be balanced against the risk of technological dead ends. Experience from the war in Ukraine shows the importance of rapid innovation and civil-military cooperation, while Swedish procurement have often been hampered by time consuming bureaucracy.

Resource strategy and oprational strategy

Resource strategy aims to provide the operational strategy with the necessary resources – people and equipment. There is a mutual dependency between resource and operational strategy, where long lead times and misjudgements can have major consequences. A fleet cannot be improvised; it takes long time to effectively organize a navy to recruit and train personnel and to procure the equipment.

The importance and limitations of technology

Technological advances and innovations have always influenced naval warfare, but technology must be robust, durable, and reliable to function in the harsh environment at sea. The number of ships and their crews is crucial for endurance and flexibility – quality and quantity must be balanced. “Silver bullet” solutions are rarely successful in the long run.

Nuclear weapons and naval aspects

This chapter discusses the role of nuclear weapons at sea, particularly continuous at sea deterrence and second-strike capabilities with strategic submarines. Nuclear weapons at sea are seen as more flexible and less escalatory than on land, but they pose major strategic and ethical challenges. For Sweden, the most important defence measure is to build general resilience and protect critical infrastructure rather than acquire its own nuclear weapons.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and drones

AI is becoming increasingly important for naval strategy and tactics, particularly for decision making support, surveillance, and command and control. AI can quickly absorb and handle large amounts of data and facilitate decision-making, but it is dependent on access to data, robust algorithms, and human control.

Drones (UAVs, USVs, UUVs) are developing rapidly and becoming increasingly important for reconnaissance, mine clearance, logistics, and offensive operations, but cannot yet completely replace manned vessels. However, they are an increasingly important complement.

People in the centre

Despite technological advances, people and their will, training, leadership, and morale are crucial to success. Fatigue, lack of training, and poor organization can lead to accidents and defeat. Diversity, equality, and inclusion contribute to a stronger and more flexible defence forces but require the right selection and training.

Leadership and strategy

Effective leadership requires both good seamanship, technical and tactical competence and the ability to build trust and morale. Studies of strategy and historical examples show that adaptability, initiative, and decentralized leadership are crucial, especially in the chaos of war.

Conclusion

Technology and innovation are necessary, but must always be combined with human competence, will, and leadership. Naval warfare is won by those who can best combine seamanship, technology, adaptability, strategy, and human resources – and who understand that war is ultimately a battle of wills.

Sweden – a maritime nation!

Look at a map of the Nordic region. What do we see? A large landmass with a hole in the middle. This hole is filled with water and is called the Baltic Sea. At the bottom left of the picture is an opening – an opening to the great oceans.

But you can also look at a map on a larger scale. Then the Nordic region appears with the Baltic Sea as a spit of land sticking out from the dominant Eurasian landmass. You can see that there is much to support Spykman’s geopolitical theory of the Rimland.This has nothing to do with poetry but means the edge of the land: the area that separates the Heartland – Russia and Central Asia – from the great oceans and the new world.

This location also explains our history.

We have been torn between sea power and land power. While the Swedish Vikings followed the rivers into the heartland in the east, Danish and Norwegian Vikings explored the great oceans and Europe’s borders with them.

Medieval trade was controlled by the Hanseatic League. There is a reason why Stockholm’s largest church is German: St Gertruds. And why Stockholm’s bourgeoisie was ruled by Germans. When Sweden gained independence from Denmark in 1521, it was thanks to the fleet that Gustav Vasa had purchased from Hansa City of Lübeck in today’s Northern Germany. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Swedish Empire expanded along the shores of the Baltic Sea from Finland, via the Baltic States and northern Poland and Germany. It was the fleet that held Sweden and its Baltic provinces together and enabled Sweden to become a maritime and regional superpower. But the Danes that sat on the Baltic approaches was the main naval competitor and they did what they could to hamper the Swedish trade.

Initially, the merchant fleet played a minor role. Unlike most other European maritime powers, Sweden’s fleet was focused on power projection rather than maritime protection. However, the Swedish merchant fleet became increasingly important, and Stockholm was a major maritime city until the early 19th century.

In the 1670s, 28 large merchant ships were registered in Stockholm. This dominance was reinforced by the Botnia trade monopoly, which required all trade with Norrland and Finland to sail via Stockholm. During the 18th century, Stockholm’s merchant fleet underwent experienced explosive growth, and by 1800 there were 685 registered merchant ships, corresponding to 40% of the entire kingdom’s merchant fleet.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Swedish merchant fleet grew steadily, and by 1830 it was larger than it had ever been during the commercially vibrant 16th century. This positive development continued throughout the 19th century, with a decline in the early 1890s in connection with the transition to steam and iron ships. However, by the end of the 1890s, there was a new upturn linked to the growth of the Swedish engineering industry.

Here too, the merchant and naval fleets were out of step. While the merchant fleet grew, the naval fleet virtually disappeared as the main task of the navy was to defend the country from an amphibious invasion from the sea in 1819.

The world wars emphatically demonstrated how important the two fleets were to defend Sweden’s livelihood. These lessons were immediately forgotten after the second world war – and effectively counteracted. Both fleets had a heyday after the Second World War. Sweden had one of the world’s largest merchant fleets and the navy had over a hundred warships – although not all of them were modern. We also had a prominent shipbuilding industry.

But from the 1970s, there was a double decline: the shipyards disappeared as the industry could not any longer compete on the market, the merchant fleet was flagged out due to high cost for salaries, and many of the bigger warships were scrapped. The period after 2004 was particularly critical, and it will take a long time before we once again have a navy worthy of the name. The decision to equip the Visby corvettes with anti-air defence missiles is extremely positive, but about fifteen years too late!

Our country’s accession to NATO means that the Swedish Navy now has new heavy responsibilities: to keep the sea lines from the Atlantic Ocean to the ports of the Baltic Sea open. This will require a lot more resources in ships and personnel. However, the navy and merchant fleet still play a minor role in the Swedish debate as long as the sea blindness continuous to prevail in our country.

As far as maritime industries are concerned, the need for better economic conditions, such as tax breaks, is well known; the Swedish maritime industry must be internationally competitive.

There needs to be a collective and accepted awareness that shipping, maritime security, and defence are strongly interlinked

Five pillars for maritime ambitions

- Cultural: Build a collective maritime awareness. This means integrating maritime history, geography, and culture into school curriculum, promoting public interest, and marketing maritime professions.

- Maritime: Maintaining a capable and technologically advanced navy is crucial for sovereignty, crisis management, and participation in international security.

- Diplomatic: Sweden as a strong trading nation must influence global maritime governance and balance national interests with collective international responsibilities.

- Economic and technical: Investing in the “blue economy” through innovation, investment, and sustainable practices is crucial for competitiveness and sovereignty.

- Scientific: Invest in oceanographic research to understand and manage marine resources, climate change, and biodiversity.

Strategic challenges and

recommendations

These maritime ambitions require that several obstacles are overcome such as:

- Too fragmented governance: Maritime policy is spread across several ministries.

Too fragmented maritime expertise: The fragmented political governance is matched by fragmented knowledge among those working in the maritime world. At the WMU (World Maritime University; run by the UN) in Malmö, Sweden has access to world-unique maritime expertise. But few Swedes study there – and even fewer become naval officers!

- The perception of the Public: There is a serious lack of maritime awareness among both among the general public and decision-makers.

- Industrial needs and labour requirements: The maritime sector faces a shortage of skills and a need to attract young talent, particularly in technical and scientific fields.

- Sustainable development: It is crucial to find a balance between the exploitation of marine resources and the protection of the environment.

Conclusion

Sweden must overcome cultural, structural, and strategic inertia a create a momentum for maritime development. Achieving this will require a long-term, integrated maritime strategy that encompasses culture, defence, diplomacy, economics, food and livelihood security and science, anchored in a renewed national and European ambition for the sea.

Sveriges två militära akademier – Kungl. Örlogmannasällskapet och Kungl. Krigsvetenskapsakademien – har gemensamt tagit fram en rapport om den svenska marinens roll i Nato, som Sverige snart kommer att vara medlem i.

Sveriges två militära akademier – Kungl. Örlogmannasällskapet och Kungl. Krigsvetenskapsakademien – har gemensamt tagit fram en rapport om den svenska marinens roll i Nato, som Sverige snart kommer att vara medlem i.